London, BBC Books, 2023. Hardback: 341 pp. ISBN: 9781785948091.

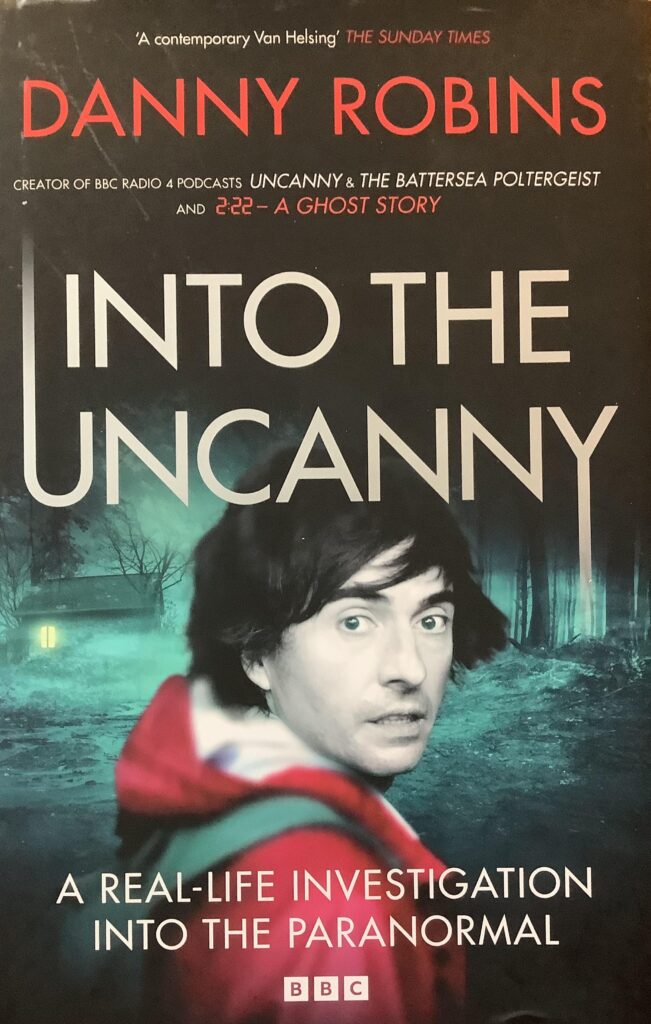

Danny Robins is on a paranormal roll. His first podcast, Haunted, based on appeals made via social media for accounts of ghostly encounters was followed in 2021 by a play 2:22 – A Ghost Story. That was followed, shortly afterwards, by a ‘breakthrough’ moment of sorts in the form of another podcast, The Battersea Poltergeist, which in turn led to an even bigger breakthrough: his wildly popular Uncanny podcast, which at the time of writing is into its third season. There have been various ‘spin offs’ along the way also, including nation-wide Uncanny roadshows, and by the time you read this review there will have been a three-part TV series on BBC2. All told, this is a remarkable set of achievements for Robins in an incredibly short space of time. Recently dubbed the ‘high priest of the paranormal’ in one national newspaper, his book Into The Uncanny takes its place alongside the other prolific output that makes up the Uncanny franchise.

In a key sense, Into The Uncanny is all about Robins: as, it could be argued, is everything else in his oeuvre. In it, we learn a lot about him: his faith-less upbringing, his fear of heights, his panic attack at age twenty whilst home from University for the Christmas break, and his current agnosticism as regards all things paranormal even though by his own admission he really wants to believe. In fact, there’s a sense in which Robins’ own quest for some kind – any kind – of transcendence is the ‘glue’ that holds his book together, compared to which the case studies it contains seem almost incidental.

But case studies there are: four in the main, with several others scattered throughout, many from the ordinary members of the public whose experiences make up the bulk of the Uncanny podcast series. In fact, the book dovetails so neatly with the podcasts that it’s like reading a written version of the cases that constitute them. Intentional, obviously, and understandable. After all: why change a winning formula?

The book begins – and, in a sense, ends – with a poltergeist case at a medieval apartment on Rome’s Via Di Monserrato , used by the Australian embassy and rented from the next door Venerable English College, a long-time training centre for English Catholic priests. Robins sometimes blurs the distinction often made between hauntings on the one hand and poltergeist manifestations on the other, but this creepy inclusio has all of the classic hallmarks of the latter: apports, disports, odd displacements of a variety of mundane objects including kitchen utensils and food, a teleported bed, and so on. I won’t spoil the ending: suffice to say that it’s something to do with the library of the college next door. Or so it seems, because the reader is left hanging, somewhat. Robins is rightly impressed with the case, although asserting, as he does, that “accounts of full-blown poltergeist activity are rare” made me wonder how familiar he is with the actual literature. They’re anything but rare, although the Via Di Monserrato case is a worthy addition to the canon.

Elsewhere we have an investigation of some creepy goings-on that affected two homes in Averham in the 1980s and 90s, a – very brief – examination of a case in which a Ouija board predicted with apparently unsettling accuracy a death (including time and cause), and a chapter on some UFO events including the celebrated ‘close encounter’ case claimed by Alan Godfrey at Todmorden in November 1980. Throughout, Robins gets out and about: to Rome, Averham, Todmorden, and elsewhere. In fact, it’s one of the strengths of the book: that he is prepared to go to the places the claimed events occurred at in order to tease out detail and nuance not always contained in testimonies alone.

Given this diligence in the follow-up to the cases chosen, it is disappointing – and a tad ironic – that so much of the material appears so superficially-handled. Robins’ description of his visit to Todmorden, for example, is interesting enough, but his analysis of Alan Godfrey’s odd experiences lacks the depth of research and critical rigour that others have afforded it. Whatever might have been the actual cause and nature of Godfrey’s close-up encounter with a strange, windowed, diamond-shaped object in the early morning of 28th November 1980, it is surely important to note the presence of an object which matches that description to a remarkable degree and which was actually in Todmorden at the time: a plastic-built ‘futuro’ home from a local firm, Waterside Plastics Ltd. Given the amount of discussion this has received, together with the fact that it offers a rather simple, down-to-earth explanation of Godfrey’s ‘encounter’, I was very surprised that Robins failed to consider it. Likewise his treatment of Godfrey’s discovery of the dead body of Zigmund Adamski on top of a coal heap at around the same time. It’s certainly odd, but there has been detailed discussion of this too and it’s far from obvious that there is any connection whatsoever between the two events.

In all, then, Into The Uncanny is something of a ‘mixed bag.’ It will no doubt sell like hot cakes but I would earnestly advise the author to ditch the footnotes in any planned sequel. Buy the book and you’ll see what I mean.

This review first appeared in The Christian Parapsychologist, New Series Vol 3 No 2, Spring 2024, pp. 50 – 2.