Ebury, London, 2022. ISBN: 9781529102550. Paperback: 348 pp.

On 31st May 2014 in Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA, two 12 year-old girls, Morgan Geyser and Anissa Weier, lured their friend Payton (Bella) Leutner, a classmate, into a forest near their homes where Geyser stabbed Leutner nineteen times (at the time, Geyser counted seventeen), failing to kill her by only the merest fraction of an inch. The conspirators left their intended victim for dead but, guided by some sort of inner voice that told her to crawl toward an open grassy area, Leutner managed to drag herself out of the forest where she was found by a passing cyclist. Many months and numerous operations later she was back at school. By this time Geyser and Weier were incarcerated and Geyser remains so to this day.

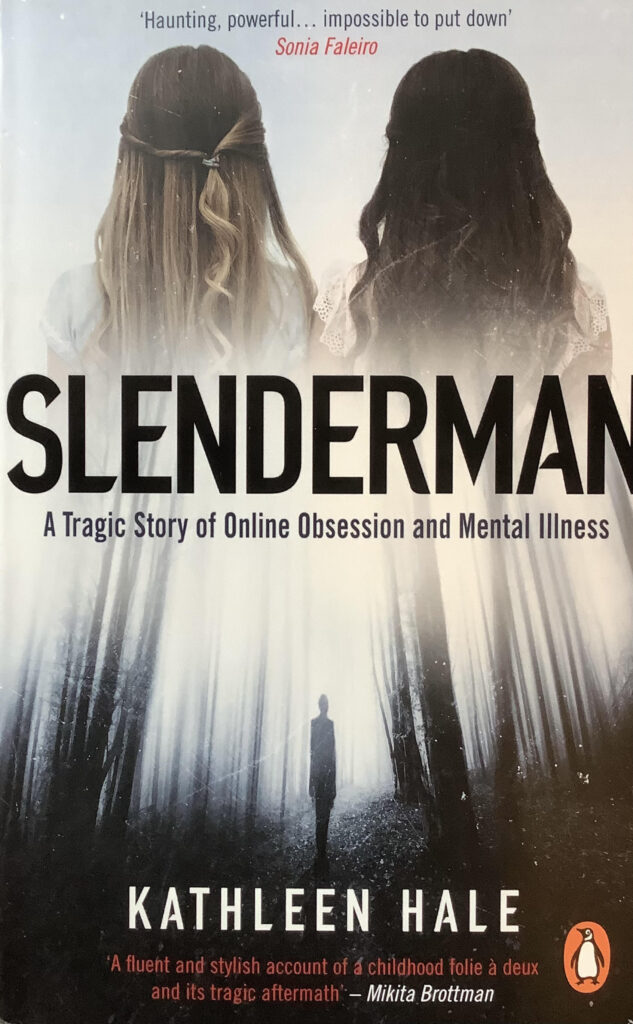

What caused the perpetrators to commit such a heinous act? The answer lies, at least in part, in the title of Kathleen Hale’s recent study of the case: the first, full-length analysis devoted to this well-publicised and most peculiar crime. For both girls believed they had to kill their intended victim to save themselves and their families from Slenderman, a tall, thin, all-black, to-all-intents-and-purposes omniscient supernatural creature with octopus-like tentacles growing from his back. Indeed, having become obsessed with him since discovering the website Creepypasta.com – devoted to short, fictional pieces on Slenderman and other fictional mythical entities – Geyser and Weier had determined to kill Leutner en route to Slenderman’s mansion in the Nicolet National Forest where they intended to live with him forever as ‘proxies.’

In the months leading up to the crime, Geyser had engaged in numerous conversations with Slenderman which Weier gave the appearance of sharing – as she did some of the alleged ‘sightings’ – and the case is sometimes referred to as classically one of folie a deux, when an apparently non-psychotic person shares the delusions of a psychotic significant other. Crucially, at the time of the attempted slaying, Geyser was (and apparently remains) suffering from schizophrenia, which, though undiagnosed in May 2014, had already manifested in various ways including Geyser’s ‘hearing’ of voices, ‘seeing’ of visions, and vivid experiencing of other powerful delusional states. Stress and isolation appear to create the possibilities for, and in turn to exacerbate, folie à deux, and Hale shows both to have been present in varying degrees in the cases of Geyser and Weier both as individuals and together as friends and co-conspirators.

When I started reading Slenderman I thought it would turn out to be of significant interest and relevance to readers of Psychical Studies – and up to a point that turned out to be the case. It raises questions, for example, about the mechanisms and potencies underlying shared worldviews at the ‘fringe’ of – and beyond – those of the mundane and the everyday. It deals with subjects that raise deep questions about what is ‘real’ and how shared ‘realities’ are constructed and maintained. And it positions itself squarely in Fortean territory in its concern with Slenderman himself: a puzzling figure that has graced the pages of that august journal on more than one occasion. I was disappointed, then, to find so many missed opportunities to engage with these and other intriguing issues.

Instead, almost half of the book deals with the court cases that ensued after the girls’ incarceration and arrest. Whilst interesting and obviously relevant to the case overall, I felt by the end that this had been overdone. The title suggested that Slenderman ‘himself’ might be in the spotlight but in the event the bulk of the book’s critical analysis ends up being concerned with the Wisconsin legal system and its perceived shortcomings – at least as far as the author is concerned – in the case of Geyser and Weier. By contrast, she shows little or no interest in any detailed discussion of schizophrenia itself, nor any inclination to examine comparable cases of childhood schizophrenia – which, as she acknowledges, is incredibly rare – nor any curiosity regarding possible parallels or otherwise between the Slenderman case and other celebrated folie à deux cases, many of them involving criminal acts such as those involving the so-called Hillside Stranglers and Witch Killers. Exploration of any or all of these avenues might have helped enhance our understanding of this in many ways remarkable case and may have relieved some of the tedium of the book’s second half which deals almost exclusively with the legal machinations surrounding the conspirators’ trials.

In short, then, this study is a mixture of ‘hits’ and ‘misses.’ It left me wanting to know more, which is no bad thing, but I couldn’t help feeling disappointed that it hadn’t quite lived up to my expectations. Another, better, book is still to be written regarding this intriguing case – one that does more than whet the appetite – but in the meantime it’s good that we’re left with at least some food for thought.

This review originally appeared in Psychical Studies, No 102, Spring 2023, pp. 32 – 4.