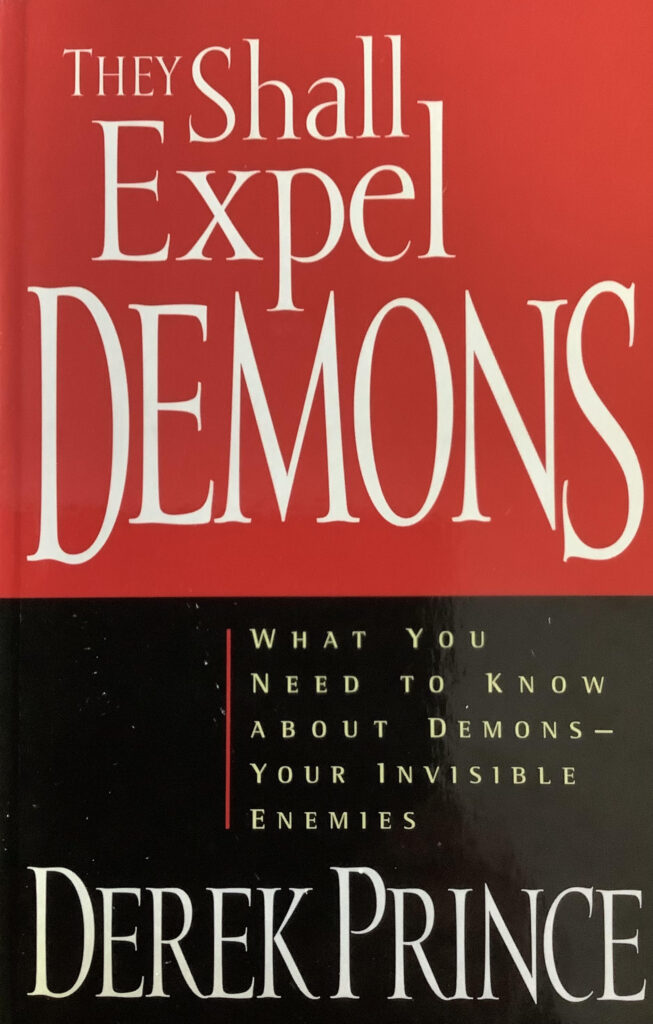

Chosen Books, Michigan, 1998; ISBN: 0-8007-9260-2 254 pp.

I found this book oddly compelling although I’m not altogether sure why. On the one hand the author, the late Derek Prince, makes some basic exegetical mistakes – which wouldn’t be so bad if those same mistakes weren’t so fundamental to his argument. For example, in showing how he came in 1953 to the conclusion that his depression was caused by a demonic ‘spirit’, he cites the opening verses of Isaiah 61, understanding a line in verse 3 – ‘a garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness’ – as a reference to an actual indwelling spirit (or demon) that was making him feel the way that he was. Given that he claims a degree of expertise in Hebrew, this is a basic error. Correctly-understood, the verse uses ‘spirit of heaviness’ not as a reference to any kind of spirit or demon at all but a kind of euphemism that might equally be translated as ‘heavy heart’. Given that this ‘discovery’ apparently opened the way to his discovery of demons underlying just about every malady from strokes to toothaches it is of more than merely passing note, being foundational for the whole worldview that ‘They Shall Expel Demons’ attempts to elaborate.

I was tempted to stop at this point – page 32 of 254 – but I was glad I didn’t because Prince raises some important questions later on, making some important points in the process. As he shows, the casting out of demons was a fundamental part of Jesus’ ministry and one carried on by the early church. Why, then, has so much of contemporary Christianity lost sight of this? And where have all of the demons gone? After all, they seem to have been very present in the ancient world and are found in numerous places throughout the New Testament. Prince’s answer to the ‘Where have they gone?’ question is that they haven’t ‘gone’ anywhere – apart from to hide. And it is in this sense that ‘They Shall Expel Demons’ serves as a sort of expose: revealing the hidden demonic forces still at work in our world whilst showing how they may be countered (literally ‘cast out’).

Another reason I found this book oddly compelling was in the way in which it articulates a world-view so drastically at variance with the one that prevails in our supposedly enlightened West. So, for example, on page 181 Prince writes, “A woman who has had an abortion almost certainly has a demon of murder, even if she did not realise that she was taking human life.” Read that one again. Yep; he really said it and appears to have actually believed it. What I find most striking about such a claim – in addition to its fundamental wrongness on just about every level – is how completely and totally against the contemporary grain it is in just about every conceivable way. Very few books manage to embody a spirit that is so antithetical to the spirit of the age but this one does.

When I just wrote that line I was using ‘spirit’ in the generally-accepted metaphorical or euphemistic sense. As in ‘the way we think and feel’. As already alluded to above, Prince uses the word ‘spirit’ in a very different way: to describe an actual entity that can indwell a human being and cause a range of maladies, including psychological and physical ones. This view violates the Principle of Parsimony, of course. Hence, when Prince writes of a young woman whose head injury opened the way for an indwelling ‘spirit of epilepsy’ to cause her subsequent fitting many would question the need for any other explanation for what that she subsequently suffered other than the purely physical one involving trauma to her brain. One wonders why the clearly highly-educated Prince didn’t consider this. Could it be because he thought he knew better? If so, who or what made him think this way?

And here’s the rub. I came away from this book thinking that I’d read a curious combination of both truth and falsehood. It was as if Prince really was onto something but at the same time had seeded his own thesis with basic errors. But were they really errors? And where had those seeds actually come from? He tells us not to believe what demons say but appears to end up reproducing a lot of what they told him anyway. Supping with the devil, as saying goes, is always better if done with a long spoon. One might add that conversing with them requires more than a pinch of salt: a lesson that the author of this book might have done well to remember.