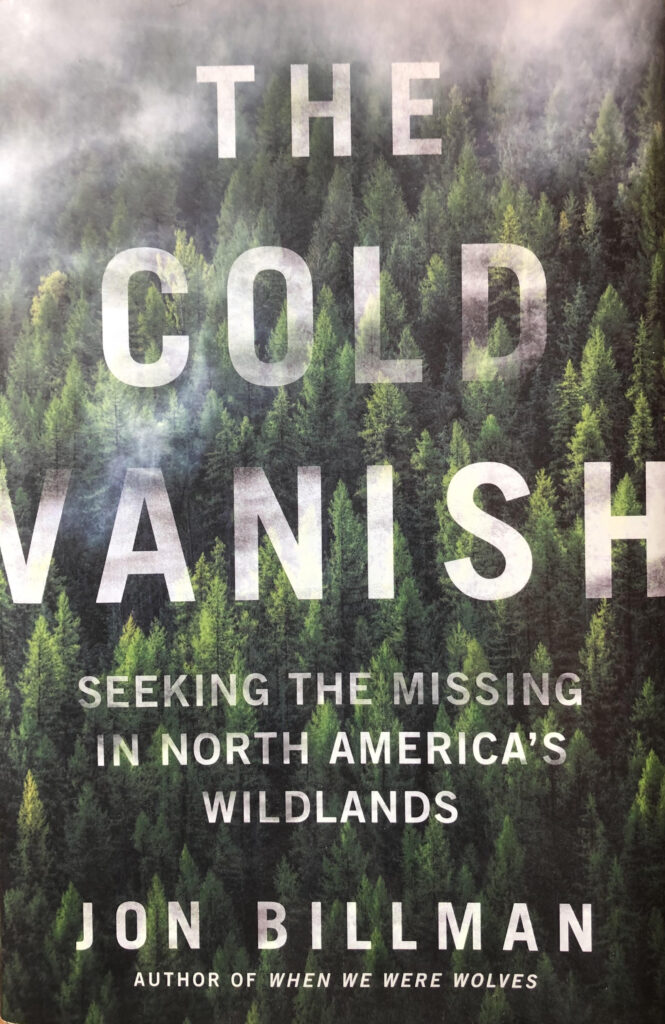

The Cold Vanish: Seeking The Missing In North America’s Wildlands by Jon Billman. Grand Central Publishing, 2020, ISBN 978-1-5387-4757-5. Hardback: 349 pp.

What of those mysterious episodes where people seemingly ‘disappear’ into nowhere – particularly within the ‘great outdoors’ such as North America’s National Parks? Jon Billman’s The Cold Vanish considers some of these strange disappearances and the result is a moving and wide-ranging travelogue as the author journeys in the company of a driven and clearly heartbroken father on a search for his missing son, Jacob Grey.

That people go missing in large numbers in American national parks comes as no surprise when you consider the sheer size of them. The Olympic National Park alone – where Jacob Grey went missing – contains 640 million acres of federal land; much of it forest. Early on, Billman tells us that nobody actually knows how many people go missing in the parks per year, but that the numbers have almost certainly been consistently underestimated: even by those such as David Paulides who have made such disappearances their literary and investigative stock-in-trade.

Although the focus of Billman’s book is the vanishing and subsequent search for Jacob Grey he gives some consideration to other missing persons’ cases too. Several conclusions follow; not least the fact that a few steps off a beaten track can turn a simple ramble into a fight for survival. Of more interest to readers of this blog, however, may be the fact that many persons choose to vanish: or, at least, to take themselves off the beaten track in search of religious and spiritual enlightenment, sometimes with tragic results. This was almost certainly the case with Jacob Grey, whose quest for enlightenment on the slopes surrounding Hoh Lake in the Olympic National Park led to his death in April 2017 at the tragically early age of 22.

Billman considers paranormal and quasi-paranormal ‘explanations’ for some missing persons cases, exploring everything from otherworldly portals and alien abductions to Bigfoot, but ultimately the tragedy behind every case is of a person who for whatever reason walks into the wilds and never returns. The book also displays a thoroughgoing knowledge of search and rescue techniques and contains some genuine shocks and surprises. I hadn’t known, for example, the extent to which red tape and problems of co-ordination hamper many search efforts, nor the extent to which many federal authorities refuse to let search and rescue volunteers self-deploy. One thing that came as no surprise, however, was the lamentable record of self-proclaimed ‘psychics’ in discovering the whereabouts of missing persons. In fact, that was one of the major take-aways from the book: if you need to track down someone who’s missing, do not employ a psychic. Bloodhounds fare rather better, but even they can hinder rather than help.

Billman’s study is well-written but occasionally overwritten and sometimes irritates stylistically. He clearly likes interviewing persons whilst they’re driving, for example, but describing a steering wheel as ‘Wonder Woman’s golden lasso of truth’ does him, or the reader, no favours. That the quest for spiritual enlightenment drives many people into solitude may come as no surprise, but that some people lose themselves – and, by extension, the world – in a quest to find themselves is but one of the ironies explored in Billman’s eye-opening and, at times, genuinely moving study. It made me want to know more about such cases but the lack of a bibliography or any references other than when he was personally involved in a search came as a genuine disappointment: hindering my own search for more detail concerning some of the fascinating cases that he chose merely to skim over.

This review originally appeared in De Numine, No. 70, Spring 2021, pp. 45-6