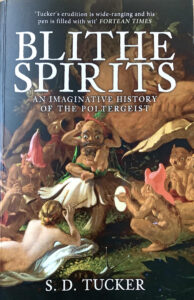

S.D Tucker, Blithe Spirits: An Imaginative History of the Poltergeist. Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2020. 352 pp. ISBN 978-1-4456-6728-7

Is there such a thing as a quintessentially English poltergeist? In Blithe Spirits, S.D Tucker argues that there is. In 1661, the Wiltshire manor-house of a magistrate named John Mompesson became the scene of a variety of extreme poltergeist phenomena following the confiscation of a drum from an itinerant beggar and busker named William Drury. The details – deafening drumming noises, sulphurous odours, terrified animals, JOTTs, odd temperature changes, and so on – will be known to anybody familiar with the annals of poltergeistery and, in fact, Tucker skims over them very lightly. (If you’re interested, you’ll find a more detailed description of what happened at Mompesson’s house in any number of other studies of poltergeists, including Harry Price’s seminal 1945 study Poltergeist Over England). So what makes Tucker’s book different? Simply this: for him, the key to unlock the mystery and meaning of such tales is to be found in the study of Tricksters. Indeed, this is his central thesis, and one which he expounds entertainingly and at length over the 352 pages of this remarkable and comprehensive book. The result is a Fortean study par excellence; one deserving to occupy pride of place on any bookshelf devoted to the exploration and study of Fort’s ‘damned facts’.

For Tucker, the account of what happened at Mompesson’s Wiltshire home constitutes nothing less than an archetypal Trickster narrative, and this recognition is key to an understanding of his thesis overall. For him, poltergeist tales show that the figure of the Trickster – encountered mythologically and elsewhere in the form of Hermes, Mercurius, Loki, King Monkey, Coyote, Wakdjunkaga, and so on – is very much alive and kicking in the twenty-first century: not as an actual being, but as a mythological personification of certain tendencies in the human mind. Tucker demonstrates this via an analysis of the poltergeist’s Trickster ‘elements’: an analysis that is remarkably detailed and well-informed. In fact, Blithe Spirits would function as a thorough introduction to the literature on poltergeists for those not acquainted with it. For those who already are, it introduces a perspective onto the study of the phenomenon which has long been overdue.

It also works as a thorough introduction to the literature surrounding Tricksters. All of the key texts are introduced and examined: from George Hansen’s seminal The Trickster and the Paranormal, via the classic studies of Lewis Hyde, Paul Radin, Karl Kerenyi and Norman Brown, right the way through to more recent examinations of the Trickster in a variety of other contexts. Tucker is obviously taken with Gef the Talking Mongoose, and references Christopher Jossife’s excellent study of him frequently and at length.

The result is a barnstorming study of the polt-as-Trickster. Tucker is careful, though, to make clear from the outset that he doesn’t believe in Tricksters per se. There is no real Trickster, he writes – “Nobody but a lunatic believes in Loki any more” – it is simply that Trickster narratives provide convenient mythological prisms through which to view ‘naughty ghosts’ such as those that bedevilled Mompesson’s home. Thus, Tricksters provide mythological personifications of the cunning and stupidity (and bawdy humour) to be found in the human mind: no less and no more. Here, alas, is the one real weakness of this otherwise excellent book. So nothing happened at Tedworth; at Willington Mill; at Enfield; at Humpty-Doo? Or at any one of literally thousands of celebrated and exceptionally well-documented poltergeist cases throughout history and world-wide? It seems to me that something did. Something with a specific ontology: however strange. Something outside of the human imagination altogether. Why not an actual manifestation of the Trickster? It ticks so many of Tucker’s Trickster boxes that I’m surprised he dismisses it so emphatically. At the outset, as well.

Of course, locating poltergeist narratives within the realm of the human imagination is not a massive deviation from what has gone before. Carol Zaleski did the same thing over two decades ago with Near-Death Experiences. What is – relatively – new, however, is using Trickster narratives as lenses through which to view poltergeist tales. I have long thought that they may provide keys to unlock the mystery of Near-Death Experiences and so was delighted to see Tucker using them to open up a different door. Books like Blithe Spirits invigorate their fields, ushering us across new thresholds as we seek to understand the anomalous and the unfamiliar. There should be more like them.

S.D Tucker, Blithe Spirits: An Imaginative History of the Poltergeist. Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2020. 352 pp. ISBN 978-1-4456-6728-7